“My dear Ertigarochka” — that’s how my grandmother Nisa (Anisya) invariably tenderly called her home. A small village in the Tyumen region, where she was born and lived for 72 years. A piece of land hidden on the left shore of the Tobol River, where once upon a time the rye was eared, people were having fun “v skladynyu” and the wind carried the sounds of children’s voices, the snorting of horses, and songs sung to the accordion.

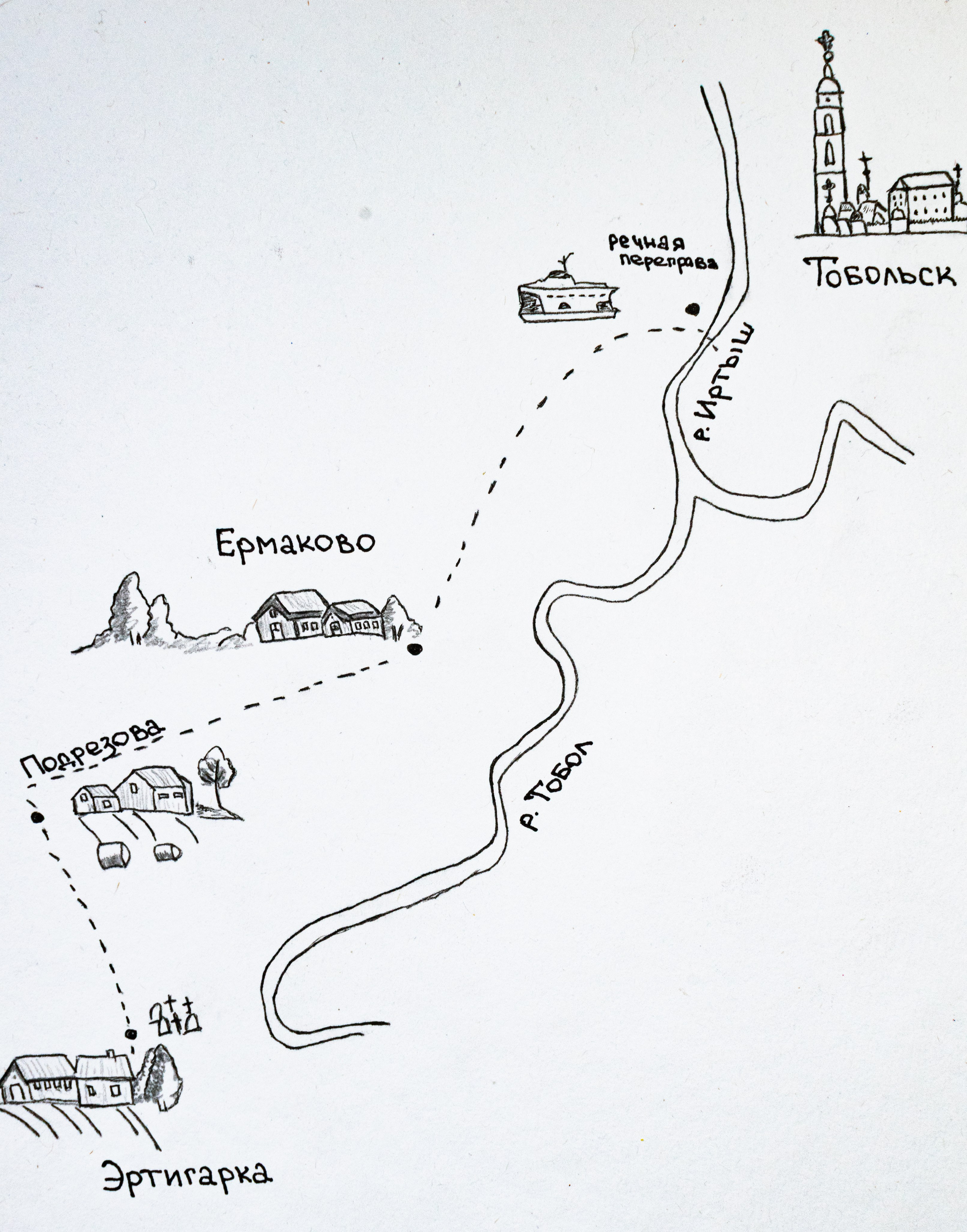

Ertigarka is located about 24 kilometers from the city of Tobolsk (Tyumen region). And although the distance is not large, in my childhood, the road to it seemed to me painfully long and frightening.

Since the village is located on the left side of the Irtysh River, in summer our path began with a ferry, in winter it passed through an ice crossing. In spring, during the ice drift, and in fall, while the ice had not yet formed, all routes to our house were cut off.

On the other side of the river was a gravel road that made your teeth knocked so hard that you could easily bite your tongue. Yermakovo, Podrezova and the turn into a dense forest where there was neither road nor sunlight. And finally, a small village cemetery and the house standing on the outskirts.

It’s still there—with its white-and-blue shutters and the bird cherry tree in the front garden.

Perhaps it is because of its inaccessibility that local historians have not heard of Ertigarka, and you won’t find this name in their monographs. Nevertheless, I did find one mention that sheds light on the origin and approximate age of the village. In the 1993 book “Tobolsk Chronograph” — one of the few things that my grandmother took from the house — my grandfather had underlined in blue ink:

Not far from the island there is a small village with a very strange name — Ertigarka. There are no settlements starting with the letter 'E' in our region at all. But in the XVIII century it was Edigarka. And if we remember that once Siberia was ruled by brothers Bekbulat and Yedigir, we can assume that the name of Yedigir’s family estate was later transformed into Yedigarka, and then into Ertigarka.

In Soviet times, Ertigarka had a farm, a “molokanka” for milk processing, a stable, a granary where grain was stored and milled, a bee apiary, an elementary school and a club. The school was closed in the late 60s, when a new one was built between the two villages — Ertigarka and Podyemka. The farm began to fall apart during the “perestroika” years, and in the 1990s, its remnants were completely looted and taken away for for scrap metal.

In 1996, my grandfather died, and after that, the house was sold for almost nothing. My grandma, unable to bear the loneliness, moved in with the children. I was 4, and I remember only the yellow door, padded with straw around the edges, the blue carpet on the wall with grazing deer, and the aluminum plate in which my grandfather used to mash boiled potatoes with a spoon.

For almost 30 years, no one has lit the stove in this larch house, which was floated down the river by my great-great-grandfather Vasily before the revolution. Even the floor has been taken out, yet miraculously, my grandfather’s cap and my grandmother’s woolen coat still hang on hooks, a cast-iron iron sits on the windowsill, and in the bathhouse, aged brooms are waiting for their owners. And it seems that memories keep the house alive. Wrapped in a snowy blanket, it seems to be sleeping, lulled by nature and the voices of those who were once happy here.

In the summer we had to graze the cows from morning till evening. I really didn’t like it. We worked in the vegetable garden, and I climbed under the barn to collect chicken eggs. When we were walking, we gathered burdock leaves to eat and lungwort. We’d go for “zemlyanka” (wild strawberries), which we later enjoyed at home with milk. As soon as the ice formed on the river, we’d lie on it and examine the bugs and grass trapped beneath. In winter, like everyone else, we sledded down the hills on sleds, “katushki”, or even on a fir tree that was left over from New Year’s.

We moved here (to Ertigarka) when my Shurik (son) was one year old. He was born in 1963. We came from Takhtair. I was just a laborer—sent wherever they needed me. In the summer, it was haymaking. As it starts, we were in the hayfields until autumn. That’s why my hands, knees, and joints ache now.

And then, when it was someone’s birthday or just like that, all the women came together in one house, they got to talking, and Aunt Nisa, being the eldest, said: “Let’s celebrate at my place today, and next week at someone else’s”. And we are six women. We’ll cook a little, bring a bottle of red wine, sit together, sing songs, talk. It’s all about good times. And what an interesting life!

Even now, when I go to bed, I sing to myself. About five or six songs, maybe around ten. I’ve memorized all the songs, I sing them all to myself. But I’m afraid to sing out loud—what if Shaitan (the devil) hears me?

Grandma Shura

People used to live together in harmony. We didn’t even lock our doors. Mom would just put a padlock on or prop a stick against the door. And everyone knew that no one was home.

When people gathered at my mom’s house, the table was always full. There were cucumbers, tomatoes, pies, stuffed fish from the oven, dumplings, meatballs.

There were no salads then, except for vinaigrette. And during feasts, we (kids) always sat on the stove, peeking out. We could only eat after everyone had left. There was so much food—pies, khvorost, pancakes, kalachiki. During Christmas time, Mom always went to Podemka to carol—imagine walking 2 kilometers just to to make people laugh. She would dress up, smear herself with soot, take a can with her. And when she came back home, that can would be filled with all sorts of things.

For 19 years, my grandmother lived in longing for her beloved “Ertigarochka”. There was never a day when she did not cry when remembering her home. In the last years of her life we often noticed how for a few days she seemed to be transported to the village and talked with long-gone relatives, friends, with those people with whom the Ertigarka land had once brought into her life. She prayed and hoped to be buried next to them, but the lack of roads made it impossible. Grandma Shura told us: “The earth is one. She will find her way.”

As for Ertygarka, out of the 25 houses that stood there in the 60s and 70s, only 15 remain today. Just five families live in the village now.